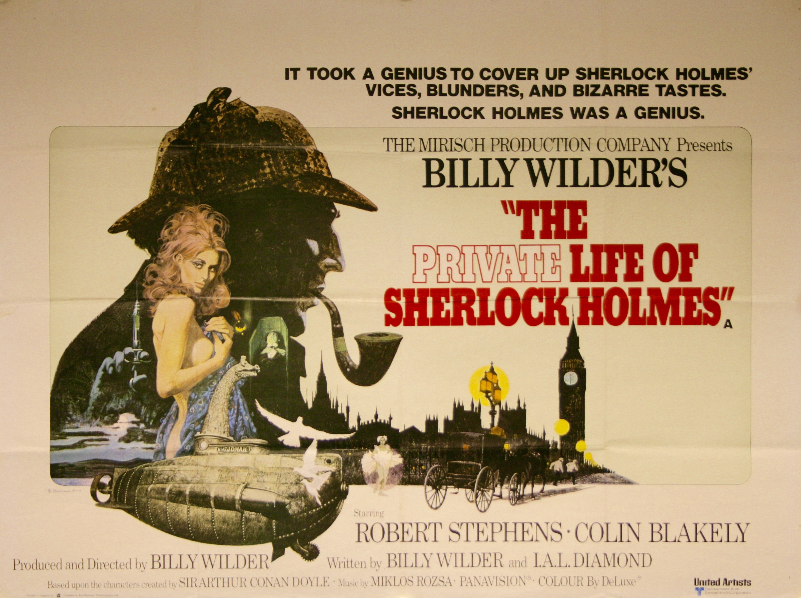

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes is a 1970 film, directed by Billy Wilder and written by Wilder I. A. L. Diamond. It stars Robert Stephens as Sherlock Holmes and Colin Blakely as Doctor Watson.

The film features two original stories by the scriptwriters and presents an unusual take on the character of Sherlock Holmes. It is an highly interesting take as well, and I want to try to analyze it in depth, so besides this being a review it is a also an analysis of the film’s themes. I’m going to discuss the film’s plot in detail, I suggest watching it before reading this, it is a really good movie.

The idea at the heart of this film is that there is a difference between the in-universe reality of Holmes and the figure presented in the stories told by Watson and published in the Strand Magazine. This conceit is supported by canon, where Holmes does complain of Watson embellishing and romanticizing the stories, and of making Holmes seem almost infallible.

This idea is used to both dramatic and comedic effect. There are several jokes about the embellishments Watson has made, which include making Holmes taller by three inches and exaggerating Holmes’s violin playing skills.

But this premise develops into a serious theme: the difference between truth and fiction, both in the form of positive ideals and cunning deceit. Tied into this is a similar conflict between idealism and cynicism. The film also wants to explore the human desire for fiction, heroes and ideals. There is an ambiguity to these conflicts, one almost personified in the film by Sherlock Holmes.

Holmes claims to resent the idealized fictions created by Watson, yet he tries to be the hero Watson thinks him to be. Holmes complains about being expected by the reading public to wear the deerstalker and inverness cape, yet he still wears them.

Part of the reason for this might be that he is in love with Watson. The first part of the film tells a story where Holmes, in order to get out of an embarrassing situation lies and says he and Watson are in a romantic relationship. Watson is furious, but the viewer is left with the suggestion that it is not just a convenient lie for Holmes. Holmes speaks of five happy years together with Watson with an air of sincere wistfulness that suggests that he privately wants a romantic relationship between them to be true. So Holmes trying to be what Watson wants him to be might be an expression of his repressed love.

Of course, that is only part of it. Holmes also wants to be the romantic hero, despite everything. He is an idealistic man on a probably doomed crusade against the evils of the world.

The plot of the film’s second story brings the idealism of Sherlock into conflict with a cynical reality. Holmes investigates a case that seems like a traditional Holmes story: a mysterious damsel in distress, Ms. Valladon turns up unexpectedly on the doorstep of 221B and asks Holmes to find her missing husband. Holmes investigates the case, but is contacted by his brother Mycroft.

Mycroft is here presented as a Machiavellian and ruthless spy master for the British government. It is extrapolated from the Mycroft of the Bruce-Partington Plans, although the lean figure portrayed by Christopher Lee is very different from the “corpulent” canonical Mycroft.

Mycroft represents the cynical counterpoint to Sherlock’s idealism. His world is one of ruthless international espionage, technology and warfare. There might be a similar interplay between fiction and reality as in that of Holmes and Watson, but here it is about the complex web of deceptions and betrayals among spies.

Mycroft orders Sherlock to drop the case of Ms. Valladon on the behalf of the interests of the British government, without explaining exactly what those interests are. Sherlock however idealistically persists in helping Ms. Valladon and investigates the case despite disapproval from Mycroft and the government. The trail leads Sherlock to Loch Ness, where the root of the mystery seems to involve a sinister scheme involving a fake Loch Ness monster. In another case of this film’s themes of deception vs reality, Sherlock and Valladon pretend to be a married couple named Ashdown.

But eventually, the person behind the sinister scheme is revealed to be Mycroft. He is testing a submarine for the British Navy, disguising it as the monster. Mycroft reveals that Ms. Valladon is actually a German spy, named Ilse von Hoffmansthal. She is using Sherlock to reveal information on the submarine. What seems at first to be a typical Holmesian mystery story reveals itself to be a subversion.

Holmes’ deductions are correct and lead him straight to the submarine mystery, but he fails to deduce the true nature of Ms. Valladon/von Hoffmansthal, thus falling into her trap.

It is especially ironic as Holmes twice in the film declares that he does not trust women, yet he commits this mistake. His assumptions are still sexist, but of a different kind. He just assumes Madame Valladon is an innocent damsel in distress because that is who he wants her to be. And that is how most his female clients in the canonical stories are like, but Ilse is not.

The irony in the film is present in the canon, where Holmes makes misogynistic statements about how “women are not to be trusted” but those words are never really borne out in his actions towards them. And while the story in the film is original, it is similar to his mistake with Irene Adler in A Scandal in Bohemia.

Despite his sexism, there is little doubt in the film that Sherlock is heroic, he is brave, intelligent and altruistic. But he is flawed in a human way, he does not always deduce the truth. And it is suggested that his heroism and idealism is not fit for the cynical modern era that is coming into being during the late Victorian era when the film takes place. It is an age of deceit he is not able to combat.

This violent and technological age is represented by the ruthless Mycroft and the submarine he is testing during the film. It is a war machine that unlike traditional battleships can kill entirely without warning. Mycroft explains that the British submarine has its equivalent among the German Kaiser, who is creating zeppelins that can similarly kill without warming, except from above.

The looming shadow of the coming world war where technology put to violent ends in the form of submarines and zeppelins would play an important role thus hangs over the film. “The Twentieth Century Approaches” as the title of an unrelated Russian Sherlock Holmes film with similar themes puts it.

But Mycroft’s submarine is opposed by Queen Victoria itself, who orders the submarine to be destroyed. It is highly symbolic that Queen Victoria herself, the very namesake of an age that encompassed most of the 19th century, is the one who literally scuttles the submarine. Her alternative is just talking to the Kaiser, who is her grandson. Her solution comes from an old-fashioned, almost medieval worldview of sportsmanship and royal family ties. Victoria’s own old-fashioned idealism, similar in kind to Sherlock’s, has a brief victory, much to Sherlock’s amusement. It is a scene that doesn’t make much literal sense, the historical Queen Victoria never had that kind of power, but as comedy affirming the film’s theme, it works.

Afterwards, having been told of Madame Valladon’s true nature, Sherlock confronts her and leads her German spy allies into a trap and her to be arrested. It is a highly ironic scene, where Sherlock pretends to have figured out Von Hoffmansthal’s deception, but of course he didn’t, Mycroft just told him. And Mycroft didn’t use Holmesian deduction to do so either, but ordinary espionage. Through trickery similar to what has in reality defeated him, Sherlock upholds the legend of himself. In a silent acknowledgement of her victory, Sherlock manages to convince Mycroft and the British government to have Ilse exchanged for a British spiy captured by the Germans.

In the film’s final scene, Sherlock learns in a letter from Mycroft of Ilse being executed while spying in Japan. And that in a kind of tribute to her experiences with Holmes, perhaps to Sherlock’s noble but doomed idealism, she had used the name Ashdown.

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes is a thematically very interesting film, as I hopefully conveyed in this essay. It is a very well-made and enjoyable film too. The script and direction is superb. The complex mood of the story is beautifully sustained, with gentle comedy with some genuinely witty and funny moments serving an ultimately elegiac and melancholy mood.

The acting is excellent, with Robert Stephens in the lead role successfully conveying the variety of emotions Holmes goes through. Colin Blakely plays a comedic and somewhat bumbling Watson, albeit one that feels intelligent compared to Nigel Bruce. Geneviéne Page is convincing as the duplicitous but far from cold Ilse von Hofmansthal. And Christopher Lee, always a commanding screen presence, is perfect for the role of Mycroft as presented in this film. Authoritative, intelligent and with an ever-present hint of scheming menace.

The film is also beautiful to look at, with some very elaborate and well-constructed sets and props by production designer Alexander Trauner that are very impressive. The location shooting in Scotland at Inverness and Loch Ness makes for some beautiful shots.

A recording of Rósza conducting an orchestral suite based on his music in the film

Miklós Rózsa’s score is excellent and plays a big part of creating the movie’s elegiac mood. It features his violin concerto, which was originally a concert piece unrelated to Rósza’s film music, plus some music composed directly for the film.

As grand an achievement, the film which is viewable today is, it is sadly not what it was originally intended to be. The film was originally intended by the director Billy Wilder to be over 3 hours long and feature four stories. There were however cuts forced by the studio that removed two of the segments and pared down the film to about 2 hours.

And none of the cut scenes survive in their entirety, with both audio and visuals intact. Which is extremely unfortunate, as the cut segments sound very interesting. One is about Watson trying to solve a case on a ship and coming to a wrong conclusion, proving how difficult Holmes’s work is. The other is about Watson constructing a fake murder mystery to occupy Holmes’s mind in order to keep him away from cocaine.

The cocaine is present in the film, one of the first Holmes films to directly show him using cocaine after the death of the Hays code. But it isn’t developed much, beyond the suggestion that Holmes’s stated reason of the drug just relieving boredom is not entirely the truth. He clearly takes it at times of emotional distress, such as in the ending when learning of Ilse’s death. And there is also a barely developed theme of Watson worrying just as in canon over Holmes’s cocaine use, here in the film taking the trouble of hiding Holmes’s supply and diluting the famous seven-per-cent solution to a five percent one.

This lack of development is probably due to that story segment being cut, which is a shame. More development of Holmes’s cocaine habit, as well as his friendship with Watson and his worries about his friend’s drug use would be interesting.

Still, even in abridged form, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes remains an interesting and highly enjoyable film. There have been more films about Sherlock Holmes than any other fictional character besides perhaps Dracula, this is one of the best.